Alexander Colquhoun, 15th/17th of Luss is an important historical and genealogical figure for several reasons. First, it was during his tenure as laird of Luss that the fateful Battle of Glen Fruin occurred on 7 February 1603. This was the culmination of a long-simmering feud between the Colquhouns and their allies on one side and the MacGregors and their allies on the other. The battle did not go the Colquhouns’ way to say the least, and several men from the Luss and various cadet branches of the Colquhoun family were killed. Fraser has more to say about Alexander than any of the other chiefs of Colquhoun, largely because of this battle.

Second, it was also during Alexander’s tenure that the Plantation of Ulster began in 1609. Under this scheme, the British crown parceled out roughly 500,000 acres of land confiscated from Gaelic Irish chieftains in Counties Donegal, Tyrone, Coleraine, Fermanagh, Cavan, and Armagh, granting individual tracts to English and Scottish landlords (“undertakers”). The goal was to install tenants who were loyal British subjects at the expense of the native Irish, and the result was the first of several large-scale migrations of Scots to Ulster that occurred in the 17th century. Sometime in the early or mid 1610s, Alexander acquired one of these grants, a tract of 1,000 acres in County Donegal called Corkagh. This paved the way for Scottish Colquhouns from various families, including Luss, to resettle in Ireland. I intend to devote a future post to the complicated history of Corkagh.

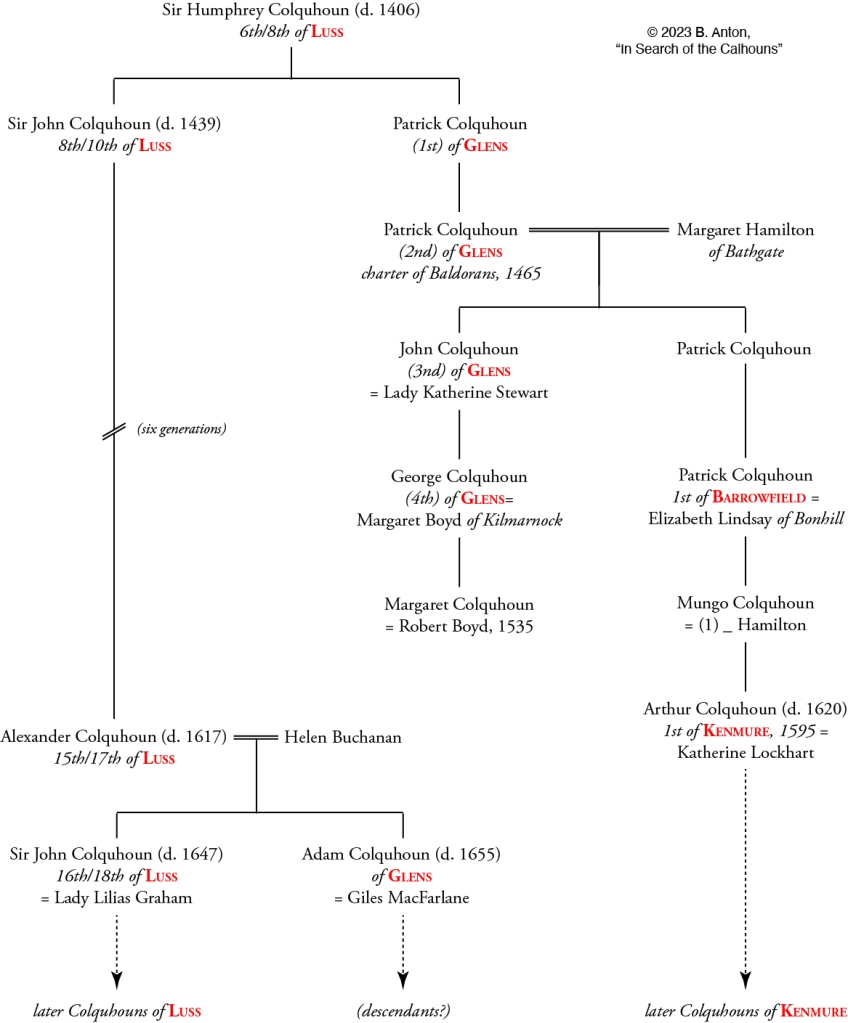

Finally, Alexander is the last (i.e., most recent) of the pre-1718 Colquhoun clan chiefs who might have male-line descendants alive today. As he was himself a male-line descendant of the family’s founder, Humphrey of Kilpatrick, he presumably belonged to Y-DNA haplogroup E-Y16733. As I outlined in a previous post, for the purposes of genetic genealogy, identifying a male-line descendant of as recent an E-Y16733 chief as possible would be of tremendous importance. In 1718, the male line of the clan chiefs came to an end with the death of Alexander’s great-grandson Sir Humphrey Colquhoun, 20th/22nd of Luss, with all chiefs after Sir Humphrey being male-line descendants of the Grant family. All patrilineal lines of descent from every chief between Alexander’s time and 1718 are also known to be extinct. Therefore, to find a documentable male-line descendant of Humphrey of Kilpatrick, we need to look to Alexander’s younger sons (most likely, to his youngest son, Adam), or to the younger sons of chiefs prior to Alexander.

Throughout this post, all citations that are simply page numbers refer to Fraser volume 1, with the rest of the reference omitted for brevity. I have seen Fraser and other 19th century historians of the Scottish clans accused by more modern scholars of “antiquarianism” and of pandering to their patrons rather than portraying historical events in an objective light. (See, for example, D. J. Johnston-Smith. “The Clan MacFarlane of North Loch Lomondside c. 1570-1800” (2002). M.Ph. thesis, University of Glasgow, p. 16.) I can’t really speak to this and won’t comment extensively on historical events like the Battle of Glen Fruin here, but as I have mentioned before, I do for the most part trust Fraser on genealogical details except where proven wrong. He is typically very diligent in detailing his own sources, so the page-number citations direct the reader both to Fraser and to the references therein.

Alexander’s Life

Considering Alexander’s importance to the genealogy of the Calhoun family, I was shocked that I was unable to find any serious analysis of what is known about his life and children beyond what appears in Fraser and The Red Book of Scotland. Identifying dates of birth, marriage, and death for him and his family would go a long way to determining which family traditions are likely to be true and which are not. Parochial records from Luss begin only in 1698, long after the births and marriages of Alexander and his children, so for the most part we must estimate these dates based on other information.

Alexander assumed the role of chief and laird in mid-1592 upon the assassination of his older brother, Sir Humphrey Colquhoun, 14th/16th of Luss (p. 153), who was at that time about 27 years old (p. 160). Alexander, meanwhile, was still in his minority in January 1592/3, since a chancery return from that time granting him power to administer the affairs of his late brother’s children states that Alexander was “of lawful age, by virtue of a royal dispensation, granted on account of his minority” (p. 168). Although a minor, we might guess that since Alexander was deemed able to manage their affairs, he was at least close to majority, so a reasonable year of birth for him is probably 1572 or 1573.

The murder of Sir Humphrey in 1592 was one of the events that precipitated the Battle of Glen Fruin some 11 years later. When Alexander became laird of Luss, he inherited several ongoing feuds, not only with the MacGregors and MacFarlanes with whom that battle was fought, but also with the Buchanans and Galbraiths. Marriage was one means of quelling feuds, and Alexander’s marriage to Helen Buchanan, daughter of George Buchanan of that Ilk, was meant to, and apparently did, put to rest the Colquhouns’ differences with the Buchanans, turning one enemy into an ally. The marriage contract between Alexander and Helen is dated 18 August 1595 at Glasgow, and a charter granting Helen liferent from the lands of Sir Humphrey’s widow, dated 15 October 1595, names Helen as Alexander’s “future spouse” (pp. 172-173). The marriage between Alexander and Helen most likely took place soon after, in the last months of 1595.

Alexander was therefore married at the age of about 22, which is slightly on the young side for that time. This relatively early marriage may have been arranged not only to settle a feud, but also to produce male heirs quickly, since by that time his two brothers were both deceased. By the time of Alexander’s death on 23 May 1617, he and Helen had twelve children, eleven of whom were named in his will dated 16-17 May 1617 (p. 230). Although he died at a relatively young age (44 or 45), the fact that he was able to draw up a will about a week before his death suggests that he died of illness as opposed to something sudden. The first of his children (son John) would likely have been born in 1596, and if we assume a child was born roughly every two years thereafter (since there is no evidence there were any twins), the last of his children would have been born about the time of his death, 1616 or 1617. Assuming Helen was of similar age to her husband, she would have been about 44 in 1616 and therefore nearing the end of child-bearing age anyway. Helen seems to have died prior to July 1629 (p. 235).

There are a few scattered references to Alexander as “Sir” and “knight.” Fraser states, “It does not appear that Alexander Colquhoun was ever knighted. Among the Luss writs there is none in which he is designated knight, although in some of the numerous official documents connected with the Macgregors he was so designated, apparently through mistake” (p. 232). One other record, not mentioned by Fraser, on which Alexander was mistakenly referred to in this way is his letter of Irish denization, issued in 1617.

Alexander’s Children

In Fraser’s chapter on Alexander, there are three lists of his children. Fraser’s numerical lists (pp. 232-238) break out the sons and daughters separately, in the following order, evidently by age: sons John, Humphrey, Alexander, Walter, Adam, George; and daughters Jean, Nancy, Katharine, Helen, Mary. Fraser also lists the younger children who were represented as executors to their father’s will by proxy (p. 230) in the order (Humphrey), Jean, Alexander, George, Walter, Adam, Nancy, Katharine, Helen, and Mary. Finally, the list of those same younger children taken directly from Alexander’s will and testament (p. 230) is in the order Humphrey, Jean, Alexander, Nancy, Katharine, Walter, Adam, Helen, Mary, and George. This last list, because it was dictated by Alexander himself, is likely to be closest to the correct order of the children’s births, and the separate orders of the sons and daughters in this combined list match Fraser’s numerical lists.

One child is missing from all of these lists, namely son Patrick. Patrick’s existence is known from the following passage in Fraser vol. 2, which I also mentioned in my previous post about Alexander’s son Adam:

John Colquhoun of Camstradden, the father of Robert, had impignorated and wadset his lands of Aldochlay, on having received in loan the sum of 200 merks Scots, from Alexander Colquhoun of Luss, who gave the same for the behoof of his son Patrick. On the death of the said Patrick, his brother-german, Adam Colquhoun of Glens was lawfully retoured and infefted as Patrick’s heir, in the foresaid lands, during the non-redemption thereof.

Fraser vol. 2, p. 202, referencing “Original Discharge and Renunciation in Camstradden Charter-chest.”

Exactly when Patrick died is not stated in the above passage, but it must have been before 1653, when the mortgage was paid off to his brother Adam. Some secondary sources state that Patrick died in Sweden in 1639, but no evidence is provided. Given that Patrick is not mentioned in his father’s will, it seems more likely that he died as a child and predeceased his father. Even if he survived to adulthood, he probably had no children of his own, since his assets (or at least, the mortgage mentioned above) passed to his brother upon his death.

If we assume the list of children in Alexander’s will is ordered by birth, the expected birth dates of the children (except Patrick) would all be consistent with other known facts about them, with one exception. Son George was last in the list, which would have placed his birth about 1616. However, he entered the University of Glasgow in 1622 and graduated in 1625 (see Munimenta Alme Universitatis Glasguensis vol. III [1854], pp. 76 and 16), so he could not have been born this late. As other university students at that time were graduating around age 19, I instead estimate George was born about 1806, making him the fourth of the seven sons rather than the youngest. This is also how Fraser places him in his list of executors by proxy. Taking the list from the will, moving George to where he probably belongs, and adding Patrick, I suggest the correct birth order of Alexander’s children, with estimated birth dates, to be as follows.

- John Colquhoun (ca. 1596-1649), first mentioned in records in January 1602 (p. 239). In various parts of Alexander’s will and testament, John is referred to as “John Colquhoun, fiar of Luss, son and heir to the said Alexander” and “John Colquhoun, his eldest son.” (The fiar was the heir-apparent to the laird, typically the eldest son.) Upon the death of his father in 1617, John became 16th/18th of Luss, and by charter dated 30 August 1625 at Edinburgh, he was granted the rank and dignity of Baronet (p. 245). In July 1620, he married Lady Lilias Graham, eldest daughter of John, 4th Earl of Montrose (p. 242). He died between February 1649 and May 1650 (p. 250).

- Humphrey Colquhoun (ca. 1598-1672). Alexander’s will calls him “Humphrey, his second son” and leaves money for him to purchase the estate of Balvie in the parish of East Kilpatrick. Despite his youth, Humphrey served as executor at his father’s probate in his own name and as representative of his younger siblings (p. 230). Sometime around 1660 he was created a knight, becoming Sir Humphrey Colquhoun of Balvie. He married Dame Margaret Somerville, second daughter of Gilbert, 8th Lord Somerville at an unknown date. His own will was drawn up in June 1672, so he probably died about that time (original copy of his probate records from Scotland’s People). He had no children (as per both Fraser [p. 234] and the probate records).

- Jean Colquhoun (ca. 1600-1677). Named as Alexander’s eldest daughter in a Latin charter from 28 July 1632: “Jeanne Colquhoun … filie legit[ima] natu maxime quond. Alexandri C. de Lus ac sorori germane Joannis C. tunc de L.” (Register of the Great Seal of Scotland, A.D. 1306-1668, charter 2056, p. 701). In support of this, her father’s will “ordains Jean to have whatever silver and gold be in his chest, over and above whatever is purveyed to her, with all the help her brother may, as he chooses, that he be first respected especially to advance her the sum of £10,000, in the name of dowry, for satisfaction of all, she disposes all benefit she might have by her father, in favor of John, who is to pay the said sum.” Additionally, John was to pay her 1,000 marks per year at Martinmas. She married three times, first to Allan, 5th Lord Cathcart, with the marriage contract to him dated 29 October 1626 and the marriage probably occurring in 1627 when she received the dowry money from John (p. 236). Her probate records, in which she is named as “Dame Jean, Lady Cathcart, par. of St. Quivox”, are dated 29 October 1677.

- Alexander Colquhoun, born ca. 1602, first mentioned in records in 1607 (p. 234). In a contract from May 1612, he is styled “third son of Alexander Colquhoun of Luss” (p. 234). He enrolled at the University of Glasgow in 1618 (as Alexander Colquhoune filius Baronis de Lus) and graduated in 1621. He married Marion Stirling before 18 June 1632, when his daughter Jean was baptized at Edinburgh. Apparently, no children survived him (p. 235).

- Nancy Colquhoun, born ca. 1604. Fraser provides no information about her. She was likely only about 13 years old when her father died and clearly not married at the time. She is said to have died unmarried (The Red Book of Scotland, vol. III. Gordon MacGregor, 2022, p. 254.)

- George Colquhoun, born ca. 1606. He enrolled at the University of Glasgow in March 1622 (as Georgius Colquhoune filius de Luss), graduating in 1625. Because his older brother Alexander graduated at about age 19, I estimate George’s birth date to be about 1606, which would place him as his father’s fourth son, in agreement with Fraser’s list of executors by proxy. Immediately after graduating, George took Thomas Fallasdaill of Ardochbeg to court to recover money owed to him (p. 235). In 1627, he made assignation of a bond stating, “John, now of Luss, my eldest lawful brother, in my necessity has contended, paid, and delivered to me a certain sum of money employed by me for settlement of certain of my debts and necessary affairs, and for my better settlement and furnishing to my intended voyage and journey to other foreign parts beyond this kingdom” (p. 236, with archaic Scots words and spellings updated by me). Fraser contends that George indeed went abroad, where he died without issue (p. 236).

- Katharine Colquhoun (ca. 1608-1696). Fraser notes a decree from Andrew, Bishop of Argyll, “dated 27th June 1632, decerned that John should pay his sister Catherine, the eldest, who was then of the age of twenty-one years, and so marriageable, the sum of 7000 merks…” (p. 248). As Katharine was “of 21” in 1632, she must have been born prior to 1611, consistent with the 1608 estimate. However, the decree is probably in error in stating she was the eldest, since the 1632 charter described above, provisions for Jean made in her father’s will, and all list orders, indicate that Jean was undoubtedly the eldest daughter, not Katharine. She married Sir John Mure of Auchindraine, as she was named as his future wife in a liferent contract dated 20 October 1632 (RMS 1634-1651, no. 1086, as cited in The Red Book of Scotland, vol. III. Gordon MacGregor, 2022, p. 254.) She lived to a very old age, as her probate records, in which she is named as “Dame Katherine, relict of Sir John Moor, of Auchindrain, burgh of Ayr”, are dated 12 May 1696.

- Walter Colquhoun, born ca. 1610. Like his brother George, Walter received money from his brother John, essentially a payout of his inheritance share, “for the furtherance of his business, and for his better outfit for foreign parts” (p. 235). This transaction was dated 27 July 1629, when Walter would have been about 19, the same age as George probably was when he graduated from university. Fraser states that, like George, Walter died abroad without issue (p. 235).

- Patrick Colquhoun, born ca. 1611. Patrick’s placement in this list is somewhat arbitrary, since he does not appear in any of the lists of children related to his father’s will. He was clearly younger than his brother Alexander (the “third son”), and given the dates when his brother George graduated college and his brother Walter received his inheritance, Patrick was probably younger than them as well. Because Patrick’s assets passed to Adam upon his death, Patrick was likely older than Adam, so I have squeezed Patrick’s birth between those of Walter and Adam here. As noted above, Patrick probably died as a child, before his father’s will was drawn up in 1617.

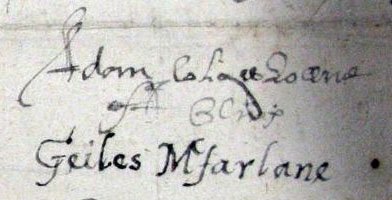

- Adam Colquhoun (ca. 1612-1655). It appears that Adam, the subject of my previous post, was the youngest of Alexander’s seven sons. Alexander’s testament states, “His will is, that notwithstanding whatever provision is made concerning the Irish lands, that Adam have the same” (p. 231, with archaic Scots words and spellings updated by me). Much has been made of Adam’s tenuous connection to Ireland, and I will treat this topic more fully in future posts. Adam’s oldest brother, Sir John, was tasked with providing for his younger brothers and sisters, and sometime around 1631, when Adam was about 19, “Sir John agreed upon a sufficient provision for his brother Adam” (p. 248). Unfortunately, Fraser does not state what this provision was, but it may have involved the purchase of the estate of Glens in Stirlingshire, since Adam was later styled, “Adam Colquhoun of Glens.” Fraser states, “In December 1634, Adam Colquhoun, brother to the Laird of Luss, was indebted to William Towart (Stewart) £42, 2s” (p. 235), so his establishment at Glens must have been after 1634 and before 1644, when he married Giles, daughter of Walter MacFarlane of Arrochar. Just as his father’s marriage quelled a feud between the Buchanans and Colquhouns, Adam’s marriage may have been arranged to quell a feud between the MacFarlanes and Colquhouns (who fought on opposite sides in the Battle of Glen Fruin) and/or between the MacFarlanes and Buchanans, Adam’s mother’s family. Adam died in 1655, as per his probate records.

- Helen Colquhoun, born ca. 1614. Neither Fraser nor The Red Book provide any information about her.

- Mary Colquhoun, born ca. 1616. Neither Fraser nor The Red Book provide any information about her. However, Fraser says, “It has not been ascertained whether Nancy, Helen, and Mary Colquhoun had ever married, although it is understood that one of them became the wife of William Cunninghame of Laigland, in the parish and county of Ayr” (p. 238). Given what The Red Book has to say about Nancy, it must have been either Helen or Mary who married William. There is a brief treatment of the Cunninghams of Laigland or Lagland on p. 210 of James Paterson’s History of the County of Ayr, with a Genealogical Account of the Families of Ayrshire (Edinburgh: Thomas George Stevenson, 1852). It mentions that William died shortly before 1 February 1643 but makes no mention of his wife.

Worth mentioning here is the fate of Alexander’s sons George and Walter, both of whom left Scotland for other lands. Where might they have gone? One possibility is Ireland, where records from the 1660s-1670s do mention a George Colquhoun in Co. Antrim and two Walter Colquhouns, one in Co. Antrim and another in Co. Donegal. However, it is not at all clear that these were Alexander’s sons as opposed to other Colquhouns of those names. Furthermore, records of the brothers state they were going “beyond this kingdom” and to “foreign parts”. At that time, England and Scotland were ruled by a common monarch, James VI/I, with Ireland considered an English possession, so my feeling is that these terms imply the brothers went elsewhere, likely to the European Continent.

The Thirty Years War, which pitted the Habsburgs and their Catholic allies against the anti-Habsburg (primarily Protestant) powers, raged across Europe from 1618 to 1648. Scotland played a significant role in the conflict, both in military and diplomatic capacities. It is possible that George and Walter left for Europe in the 1620s as military officers or diplomatic officials. (The same might have been true of Patrick, if in fact the claims of him dying in Sweden in 1639 are correct.) There is no further record of George or Walter that I can find, and I suspect that Fraser’s statements that they died without issue were based on recollections of the Luss family and not on written records.

Alexander’s probate records merit a post in and of themselves, so I will wrap up here and save that for next time. As always, if you have any evidence that refutes or supports any of what I’ve said here, be sure to let me know.

*****

© 2023 Brian Anton. All rights reserved.

*****