The Importance of the Crosh Family

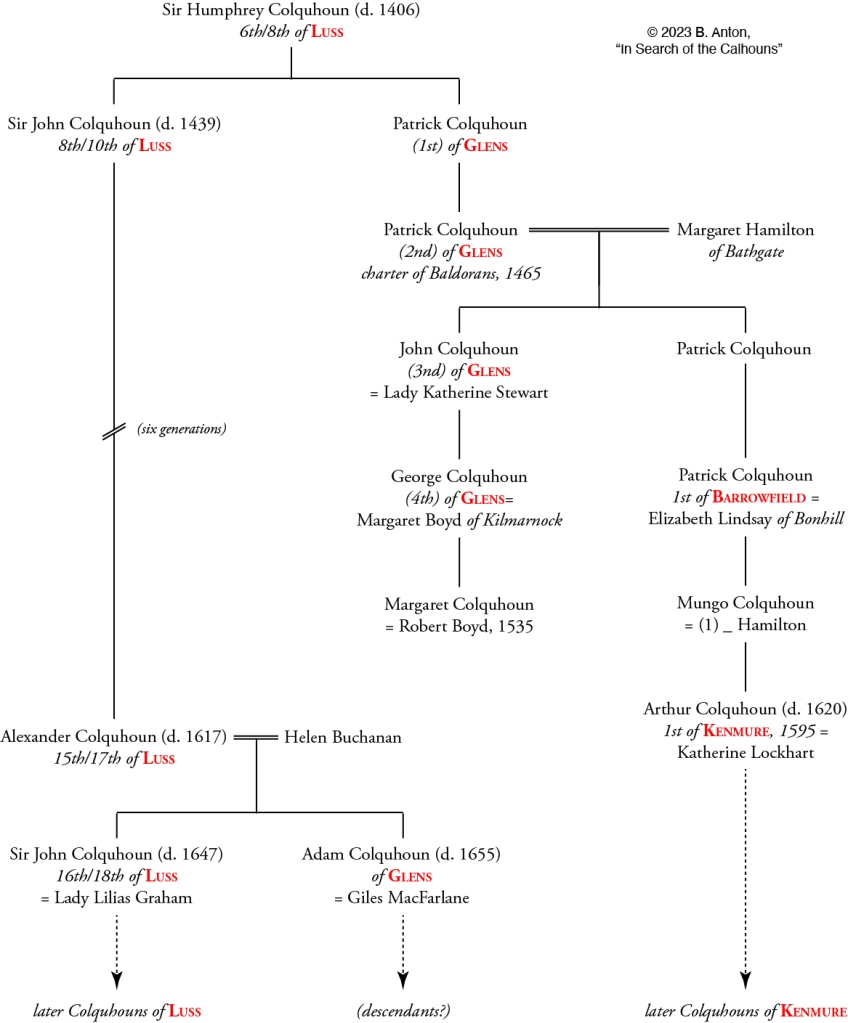

Of the Colhouns of the Irish gentry, undoubtedly the most well-known group came to prominence near Newtownstewart, parish Ardstraw, County Tyrone, a family I refer to as Colhoun of Crosh. (I realize this term does not accurately describe the family as a whole, but it is a heck of a lot more convenient than referring to them as “The descendants of James Colhoun of the Newtownstewart area, one particular group of whom later lived in a manor house in the townland of Crosh in County Tyrone.”) They owe much of their renown (among genealogical researchers, at least) to a book published in 1904 by Charles Croslegh, who was himself a member of that family. The pedigree that Croslegh proposed shows his family to be the patrilineal descendants of Alexander Colquhoun, 15th/17th of Luss, the first well-documented Scottish Colquhoun landowner in Ireland. Because William Fraser had in 1869 published a pedigree of the Colquhoun of Luss family stretching from Alexander all the way back to the Colquhoun family’s 13th-century founder, anyone claiming descent from the Colhoun of Crosh family in Ireland could boast of an unbroken pedigree back to the year 1240 or so.

The idea of an unbroken pedigree back to Luss proved too tempting to resist for many Calhoun genealogists, whether amateur or professional, casual or serious. Many Calhouns left Ireland for the Americas and other parts of the British Empire in the 18th century as part of the Ulster Scot migration, and modern-day descendants of those emigrants who try to trace their ancestors often find their paper trails end at the Atlantic Ocean. Because Croslegh’s has been the most readily accessible pedigree of Irish Calhouns from the 17th and 18th centuries, many of these modern-day descendants make the assumption that their immigrant ancestor belonged to the Colhoun of Crosh family. And why wouldn’t they? Doing so would not only allow them to claim specific 18th-century ancestors in Ireland, but would seemingly join their family to a ready-made pedigree stretching back an additional 500 years.

As I have tried to lay out in previous posts, there are two problems with this. The first is that the Colhouns of Crosh were only one of many Calhoun families in Ireland in the 17th and 18th centuries, each founded by a different settler from Scotland; therefore, it stands to reason that most Calhouns of the Irish diaspora are not closely related to the Colhouns of Crosh. The second is that even if one’s connection to the Crosh family were to prove true, the part of Croslegh’s pedigree connecting the Colhouns of Crosh in Ireland to Alexander Colquhoun of Luss in Scotland is seriously flawed. I described all the reasons why in two earlier posts (here and here), so I direct anyone interested to those articles rather than repeat the reasoning here.

In the last section of a previous post, I discussed the importance of finding at least one living Calhoun with both a genealogical and a Y-DNA genetic connection to the family’s 13th-century founder, Humphrey of Kilpatrick: it would enable us to at least begin to map William Fraser’s extensive pedigrees onto the Y-DNA genetic tree, thus helping to interpret the ancestry of many modern Y-DNA testers. While the senior Scottish Colquhoun families have all died out in the male line, many people pointed to Croslegh’s pedigree as providing a critical male lineage through an Irish branch of the family. If my posts managed to convince you that Croslegh’s proposed connection between the Crosh and Luss families is not correct, then we were stuck, since to my knowledge at least, there was no alternative.

This left us in the following quandary. We had a number of living people who could claim genealogical descent from Humphrey of Kilpatrick, including the present-day Colquhoun lairds of Luss, but none followed the Calhoun male lineage continuously, meaning their Y-chromosome is not inherited from the earliest Colquhouns. Conversely, we had many others who could claim genetic descent from Humphrey in the male line, namely those men belonging to Y-DNA haplogroup E-Y16733, but none had a well-supported, unbroken genealogical connection to him. Therefore, we had people who could satisfy each one of our two necessary conditions, but no one who could satisfy both.

As it turns out, I believe we do have a group of living Calhouns that satisfies both conditions, and it is … the Colhoun of Crosh family! I have now managed to construct a new genealogical connection between the Crosh and Luss families. It is quite different from the one Croslegh proposed, but in my opinion, it is well supported by evidence. Furthermore, those of the Colhoun of Crosh family who have tested do indeed belong to Y-DNA haplogroup E-Y16733. We’re back in business!

I originally envisioned writing a series of two or three posts about the Crosh family, the first of the Colhoun families of the Irish gentry that I planned to tackle. However, it was in the course of writing and researching this first post that I discovered what I believe to be the family’s true origins in Scotland. To thoroughly discuss not only the various generations of the Crosh family in Ireland but also this new proposal will now probably take five or six posts altogether. Oh, well. In this first post of the series, I will discuss the family’s earliest days in 17th century Ireland and the other Calhouns from that time who may have been related to them. In the next two posts, I will lay out my new proposal and invite feedback, so stay tuned!

The Mountjoy Family

The Colhouns of Crosh can be traced in Ireland back to 1631, when they were living on the manor of Newtownstewart in County Tyrone. Newtownstewart was named for Sir William Stewart, the senior-most owner of the property at that time. A Servitor who came to Ireland in the early days of the Plantation and diligently developed his land, Sir William was rewarded with numerous properties, including Newtownstewart. His descendants in the Stewart and Gardiner families were elevated to the peerage, and for simplicity, I will often refer to this family in its entirety as the Lords Mountjoy or the Mountjoy family. Subsequent generations of Mountjoys added to the family’s holdings before all of it was finally sold off in the mid-19th century.

As a family of the gentry, the Colhouns of Crosh had ownership rights to various properties, but property rights were multilayered in those days, and their rights to most if not all of their holdings seem to have been subordinate to the Lords Mountjoy. Before discussing the Colhouns themselves, I want to describe those of the Mountjoys’ holdings in the Counties of Tyrone and Donegal most relevant to the Colhouns:

- Manor of Ramelton and Fortstewart (parish Aughnish, barony Kilmacrenan, Co. Donegal). Originally the manor of Clonlarie [Glenleary] granted by patent in 1610 to the Servitor Sir Richard Hansard, it quickly passed to Sir William Stewart to become his first Irish holding.

- Manor of Tirenemuriertagh [Tirmurty] (parishes Cappagh and Bodoney Lower, barony Strabane Upper, Co. Tyrone). Originally granted by patent to James Haig, it was surrendered in 1613 to joint ownership of Sir William Stewart and George Hamilton.

- Manor of Mountstewart (aka Aghanteane, aka Rashmount Stewart; parish Clogher, barony Clogher, Co. Tyrone). Originally the manors of Ballyneconolly and Ballyranill granted to Edward Kingswell, Esq., probably a Servitor. Kingswell sold these lands in 1616 and they were enfeoffed to Sir William Stewart shortly thereafter. Except for a single mid-19th century marriage record, I have found no Colhouns living in parish Clogher.

- Manor of Newtownstewart (parishes Ardstraw and Cappagh, baronies Strabane Upper and Lower, Co. Tyrone). Originally the manors of Newtown and Lislap granted to James Clapham in 1610, they were soon transferred to Sir Robert Newcomen, from whom they passed by inheritance to his son-in-law Sir William Stewart in 1629.

- Part of the manor of Wilson’s Fort (aka Killynure, aka Cavan; parishes Convoy, Raphoe, and Donaghmore, barony Raphoe, Co. Donegal). Originally the estates of Aghagalla and Convoigh [Convoy] granted to the Wilson family, it was around 1661 inherited by a descendant, Charles Hamilton, son of Andrew Hamilton, Esq. In 1676, a portion went to a Wilson relative, Capt. John Nisbitt of Tullydonnell, and the rest was sold in 1712 to Col. Alexander Montgomery of Croghan, Co. Donegal. Part was soon after acquired by the 2nd Viscount Mountjoy. (Marilyn Lewis. “William Willson: From Clare to Donegal.” Ivan Knox, “The Houses of Stewart from 1500-” (2003), pp. 24-25.)

With the exception of Mountstewart, Colhouns lived or held property in all of these places (such as the townland of Crosh itself, which belonged to the manor of Newtownstewart). Because of the Colhoun of Crosh family’s long association with the Mountjoys, it is worth considering that Colhouns living on any of these Mountjoy estates––not just Newtownstewart––prior to the mid-19th century might have been related to the Colhouns of Crosh.

James Colhoun and Alexander McCausland

A 1631 muster roll of men living on Sir William Stewart’s estates in Co. Tyrone includes the following names, located relatively near each other on the long list:

- 80. James Cacone, sword and pike

- 111. Alexander McCaslane, sword and snapchance

As I mentioned in a previous post, despite the butchering of the names, I believe these two men to have been James Colhoun and Alexander McCausland (the presumed future father-in-law of James’s son William), respectively. As they were considered old enough to fight in 1631, I estimate that both men were born between 1600-1610. Given that time frame, both men were probably born in Scotland. Unfortunately, the muster roll does not specify which townland, or even which manor, these tenants were living on. However, both the Colhoun of Crosh and the McCausland families later lived in the vicinity of Newtownstewart, so my best guess is that Alexander and James were living in that portion of the manor of Newtownstewart lying in parish Ardstraw.

Alexander McCausland was a soldier in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, ultimately siding with Oliver Cromwell, and through this service he became entitled to a share of forfeited land in 1653. “[Alexander] obtained a commission in the army, in time of the civil wars, in the reign of king Charles I. At the end of those wars, partly by debenture, partly by purchase, he acquired the estates of Resh and Ardstraw in the county of Tyrone” (William Buchanan of Auchmar. A Historical and Genealogical Essay upon the Family and Surname of Buchanan. Glasgow: William Duncan, 1723, pp. 274-5). Alexander’s land holdings in County Tyrone included the following:

- Manor of Ardstraw (parish Ardstraw, barony Strabane Lower). Also known as the Termon, Erenach, or Churchlands of Ardstraw, this property was leased from the Bishop of Derry starting sometime prior to 1674. It appears that the McCauslands’ rights to Ardstraw were subordinate to the Earls of Abercorn.

- Manor of Mountfield (parish Bodoney Lower, barony Strabane Upper). This property was first purchased or leased by the McCauslands from Sir Henry Tichbourne of Blessing in 1658 (patent rolls #3455, 18 Jun 1658, Merze Marvin Book, James II, p. 43). Alexander McCausland’s will states rent was owed to Sir William Tichbourne, suggesting the McCauslands’ rights remained subordinate to the Tichbournes’.

- Manor of Rash (parish Cappagh, barony Strabane Upper). Located in the southern part of parish Cappagh. The townland of Rash was later called Mountjoy Forest, and it appears that the McCauslands’ rights to this property may have been subordinate to the Mountjoys.

Alexander’s will of 1674 states that his daughter Catherine was married to William Colhoun of Newtownstewart, who I presume was the son of the James Colhoun with whom Alexander appears on the muster roll.

The association between McCauslands and Colquhouns can be traced back to at least 1395 in Scotland, when John McAuslane of Caldenoch witnessed a charter in which Humphrey Colquhoun, 6th/8th of Luss granted the lands of Camstradden to his brother Robert. In 1631, the Colquhoun lairds of Luss were the immediate feudal superiors of the McCausland barons of Caldenoch, the family from which Alexander came. While it is by no means clear that James Colhoun was closely related to the Colquhouns of Luss, based on the long-standing connection between their ancestral Scottish families, it is certainly possible that James Colhoun and Alexander McCausland were friends and/or kinsmen in addition to being neighbors. Given the marriage between their children, the two men were probably also of similar social standing. Since Alexander was the supposed grandson of one of the barons McCausland, it seemed likely that James belonged to one of the Colquhoun families of the Scottish gentry. Initially, I tried to identify a candidate for James among the “missing links” of the various senior Scottish Colquhoun families, but to no avail. Eventually, I was able to determine that he was indeed from the Scottish gentry, as I will detail in an upcoming post.

At the risk of creating a new false narrative, (look out!) here come my unproven speculations. Alexander McCausland served in the army in the 1640s, likely as a middle-aged officer, and was rewarded with Irish property. James Colhoun, meanwhile, disappears from all records after the 1631 muster roll. My working hypothesis is that James either died in the Rebellion of 1641 or served in the army alongside Alexander McCausland and died in the ensuing war, in either case leaving his son William Colhoun an orphan, or at least fatherless. I speculate that after James’s death, the McCauslands “took charge” of William’s upbringing, in which arrangement William had the opportunity to meet and marry Alexander’s daughter. This scenario seems to me a plausible origin of the oral tradition handed down in the Colhoun of Crosh family (as related by Croslegh on p. x of his book) that states the family’s “first ancestor in Ireland … had come from Luss, as a child, under the charge of his uncle MacCausland.” Alexander McCausland was married to Jane (aka Janet, Jennett, Gennet) Hall, but we do not know anything about James Colhoun’s wife. While it is possible that she was a McCausland or a Hall, making Alexander a true uncle of William, I think it is equally possible that Alexander was more distant kin or even a family friend, with the oral tradition casting him as an “uncle” as a term of affection.

Again, Alexander McCausland was probably born between 1600-1610; William Colhoun was probably born about 1635 and married Alexander’s daughter Catherine about 1660. Records of the two men include the following (note that the 1659 Pender’s Census for County Tyrone does not survive):

Commissioners appointed for Poll Money Ordinances:

- 1660, County Tyrone, includes William Cahoon and Alexander mac Castguile (p. 627).

- 1661, County Tyrone, includes William Cahoon and Alexander mac Castlan (p. 646).

Hearth Money Roll, Co. Tyrone (1666):

- Rathkelly [Rakelly], parish Ardstraw, William Colhoune, 1 hearth.

- Lisnaresh [Lisnacreaght], parish Cappagh, Alexander M’Causland, 1 hearth.

Alexander McCausland’s Will

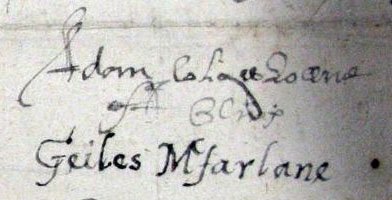

Fortunately, complete transcripts of the will of Alexander McCausland, Esq., dated 11 January 1674 and probated 1 July 1675, have survived the centuries (PRONI D669/29D). Here are a few of the relevant highlights:

- To his “dearly beloved wife Jennett McCausland” he leaves half his moveable property and one third of the rents from the manors of Ardstraw and Mountfield. She is to pay the proportionate share of the rents due to the Bishop of Derry and Sir William Titchburne, Knt. on these manors, respectively.

- To son Oliver McCausland he leaves the other half of his moveable property, plus the rights to the manors of Ardstraw and Mountfield with the exception of several townlands left to son Andrew. Rent profits to be paid to his wife.

- To son Andrew McCausland £150; the outright ownership of the townland of Eskeradooey (parish Cappagh); the reversion of the leases of John Cunningham, Gent. for the townlands of Cullion and Lislap (parish Cappagh) in manor of Mountfield; rights to “the two towns of Aldclife” [Altcloghfin, parish Errigal Keerogue ?] and the townland of Ballykeel (parish Cappagh) held by lease from Lord Mountjoy.

- To daughter Anne McCausland £150.

- “I leave and bequeath to my grandchildren, viz., Alexander Coulhound and Gerrard Colhound £100 sterling English money equally to be divided between them, which I do hereby ordain and appoint my son Oliver McCausland to pay to them, and if it happen that they or any of them die that then the said sum to be paid by my son Oliver to the rest of the children begotten to be betwixt my daughter Catherine and my son in law William Colhoune.”

- Should Oliver and Andrew and their heirs die, the manors of Ardstraw and Mountfield to be divided equally among his daughters Catherine Colhoun, Margery McClenahan, and Ann McCausland, “always reserving thereout to my daughter Catherine Colhoune more than to any other of my said daughters the castle of Ardstreagh with the other House, Gardens, Orchards, and two Parks adjoining to the Bridge of Ardstreagh” in addition to her equal share in the remainder.

- Appoints sons-in-law William Colhoun of Newtownstewart and David McClenaghan of Newtownstewart, and son Oliver McCausland, as executors.

- Appoints his “truly and well beloved friend[s]” Sir William Stewart, Bart. [Lord Mountjoy], John Colhoune of Letterkenny, John Johnston of Clare, and John Logan the Elder of Newtownstewart as overseers of the will.

- Witnessed on 11 January 1674 by John Logan, Peter Colhoune, and John Logan Jun’r.

From the will, we know that his eldest daughter Catherine married William Colhoun of Newtownstewart and that they had two children by that time, Alexander and Gerrard. It appears that these two were William and Catherine’s only children at that time, since he also held out the possibility that the couple might have more children in the future. We also know that among his trusted associates were two other Colhouns: John Colhoun of Letterkenny and Peter Colhoun of unstated residence. What are the odds that he would have such close ties to other Colhouns, at least one of whom was living a considerable distance away in Letterkenny, unless they were close relatives of his son-in-law William?

John and Peter Colhoun

The following Irish records mention a John and/or Peter/Patrick Colhoun that I believe refer to the men of those names in Alexander McCausland’s will. (As I have mentioned before, the names Peter and Patrick have highly similar Gaelic cognates and were often used interchangeably in those days.)

Prerogative will of Sir William Sempill of Letterkenny, dated 12 May 1644 (transcribed in Betham’s genealogical abstracts.): “To my servant John Colhoune, £18.” Witnesses to the will included Rev. Preb. Alix’r Coninghame, and John Colhoune.

Pender’s Census (1659): names Peter Colhoune and John Colhoune, Gents., of Letterkenny town (see p. 54). Also associated with them was Levinis Semphill.

Hearth Money Rolls (1660s):

- 1663 and 1665, Co. Donegal, Barony Kilmacrenan, parish Aughnish, Aughnish. John Colhoune.

- 1666, Co. Tyrone, Barony Strabane, parish Ardstraw, Lisnaman (Newtownstewart). Peter Colhoune.

Will of Henry Wray of Castle Wray, Co. Donegal, dated 9 August 1666 (Charlotte Violet Trench. The Wrays of Donegal. Oxford: University Press, 1945, p. 60.): mentions Henry Wray is to be buried in the church of Letterkenny, and names his wife as Lettice née Galbraith. A John Colhoune served as witness to the will.

List of representatives to the Laggan Presbytery during the period 1672-1700 (Rev. Alexander G. Lecky. In the Days of the Laggan Presbytery. Belfast: Davidson and M’Cormack, 1908, p. 144.): a John Colhoun was named as representing congregations at Donaghmore and Letterkenny as a Presbyterian elder or commissioner.

Chancery Bill, dated 25 Oct 1684 (PRONI T280, pp. 62-63.): Plaintiff Patrick Hamilton, Gent. Defendants Thomas McCausland (of Claraghmore, Co. Tyrone), Oliver McCausland, and John Colhoune. Defendant Thomas McCausland sold to the plaintiff his half-interest in the town of Drumragh in the Barony of Omagh, on lease from Bishop of Derry, for £131 on 23 Aug 1684. Will of Alexander McCausland left half-interest to son-in-law William Calhoune, other half in dispute but claimed by defendant Thomas McCausland, Alexander’s grandson, now age about 29 but a minor at the time of the will. Although the plaintiff paid the money, the defendant and his trustees, Oliver McCausland and John Colhoune, have refused to execute the deed.

Will index entries:

- Patrick Colhoun, Aughnish (townland or parish), Co. Donegal, 1703.

- Patrick Colhoune, Ardrummon (parish Aughnish), Co. Donegal, 1704.

An analysis of these records now follows.

John Colhoun appears first in 1644 and last in 1684, so we might estimate he lived in the general range 1610-1685, of similar age to James Colhoun of Newtownstewart. John appears in three wills, all associated somehow with Letterkenny. In the will of Sir William Sempill from 1644, John is described not only as a witness, but also as Sir William’s “servant”, to whom he left a small bequest. The other witness, Rev. Alexander Conyngham (d. 1660), was the Dean of Raphoe and a powerful and influential cleric in the Church of Ireland. This, along with the fact that John was a Gentleman, i.e. had some social standing, suggests John was not a menial servant but rather served in some administrative capacity, perhaps as Sempill’s estate agent. Importantly, not only was Sempill the owner of the Manor of Letterkenny (later the Manor of Manor-Sempill) and other lands in Donegal, but he was also the son-in-law of Sir William Stewart of Ramelton, owner of the manors of Ramelton in Donegal and Newtownstewart in Tyrone (see the tree of the Mountjoy family above).

In 1659, Pender’s census lists among the ten titled land-owners in Letterkenny, John and Peter Colhoun, Gents. Also with them were Rev. Alexander Conyngham (co-witness with John Colhoun on Sempill’s will) and his son James, and Levinis Sempill (not a son of Sir William, but presumably a relative). These names suggest this is the same John Colhoun who witnessed Sempill’s will in 1644, and that he and Peter were associated and likely related.

In both 1663 and 1665, the Hearth Money Rolls for the Barony of Kilmacrenan, Co. Donegal show a John Colhoun in Augnish, parish Aughnish. This was on the lands owned by the Mountjoy family, close relatives of Sir William Sempill, suggesting this is again the same John. About that same time (1666), John was a witness on a second will, that of the young Henry Wray, from a land-owning family related to the Gores and Galbraiths. Wray lived at Castlewray and Bogay in parish Aghanunshin, which is sandwiched between parish Aughnish to the north and Letterkenny to the south.

The last records of John of which we can be relatively certain are his appearance on Alexander McCausland’s will in 1674, where John is described as “of Letterkenny,” and a chancery bill from 1684 to resolve a disputed claim from that will. Whether he was the same person as the John Colhoun of Letterkenny who was a Presbyterian elder during that period is less clear. Most of John’s other known associations were with solidly Anglican gentry, namely the McCauslands, Stewarts, and Conynghams. However, it cannot be ruled out.

Peter Colhoun first appears in Pender’s census in 1659, when he and John were among the tituladoes of Letterkenny. At the time of the Hearth Money Rolls (1663-1666), Peter is found only in County Tyrone (1666), when he was living in Lisnaman (which probably referred to Lislas, the original name of the townland of Newtownstewart), parish Ardstraw. He was likely still living there in 1674 when he served as witness to the will of Alexander McCausland. However, he may have later returned to Donegal, since will index entries for a Patrick Colhoun of parish Aughnish can be found in 1703 (Aughnish, parish or townland) and 1704 (Ardrummon townland in parish Aughnish). (These two entries may refer to the same person, since the 1703 entry is for a testamentary and the 1704 entry for an administration bond.) If we assume that the Peter of Pender’s census was born about 1630, he could certainly have died around 1703. Both Aughnish in Co. Donegal and Newtownstewart in Co. Tyrone were Mountjoy properties, and movement back and forth between properties under the same landlord is not unreasonable.

If in fact Peter were born about 1630, he was of an age to have been a son of James and brother of William Colhoun of Newtownstewart. Despite the fact that Peter lived near William in 1666, I think this is unlikely for two reasons. First, it appears that Peter lived near John in Letterkenny before moving to parish Ardstraw, suggesting a closer association with John. Second, the name Peter/Patrick does not appear among William’s known descendants. I therefore think it is more likely that Peter was a son of John (or perhaps a brother or some other relationship). Finding John and/or Peter on the 1631 muster rolls would have been very informative, but unfortunately the rolls for the Barony of Kilmacrenan in Donegal (where he/they would most likely have been living at that time) have not survived. Finally, although I think it is unlikely that Peter was a brother of William, I do think it is quite possible that John of Letterkenny was the brother of James from the Newtownstewart muster roll.

Either way, both James and John appear to have been Scottish natives, meaning that to date, Colhoun of Crosh is the only Irish Calhoun family for which we can name the Scottish founder(s). Now if only we could place them in Scotland….

Are you aware of any other records pertaining to James, John, and Peter/Patrick Colhoun? Can you shed any further light on the relationships between them? If so, I’d love to hear from you!

*****

Special thanks to Paul Calhoun and Mike Barr for critical reading of this post and helpful edits, and thanks as well to Matthew Gilbert for the photos of Alexander McCausland’s will.

*****

© 2024 Brian Anton. All rights reserved.

*****

For a list of posts, visit The Genealogy of the Calhoun Family homepage.